One of my favorite Charlie Russell stories comes from an essay by Rick Newby called “Bookmen of the Montana Frontier:”

“Early in the twentieth century, Montana folklore has it, a Helena couple visiting Paris stumbled upon Charlie Russell in the galleries of the Louvre. Russell greeted them warmly but begged them not to mention to anyone back home that they had caught him shamelessly studying the works of the masters in the capital of the decadent and the effete.”

Poor Charlie, who went to such great pains to develop the persona of a no-frills cowpuncher, caught acting like a serious artist!

For those of you who don’t know, Charlie Russell came to Montana in at the age of 16. During the first 10 years, he worked as a cowboy, and spent some time living with the Blood Indians. In those 10 years, he fell in love with Central Montana and the Judith Basin, and many of his later works use that area as a backdrop. He got married in the 1890s. As an artist, that was probably the best thing that could have happened to him. His wife Nancy was an astute businesswoman and promoter, and managed to turn Charlie’s hobby into a full time business. The business that would support them for the rest of his life. Called the “Cowboy Artist,” Charlie became one of Montana’s most famous and well loved residents, and the archetype of the western painter.

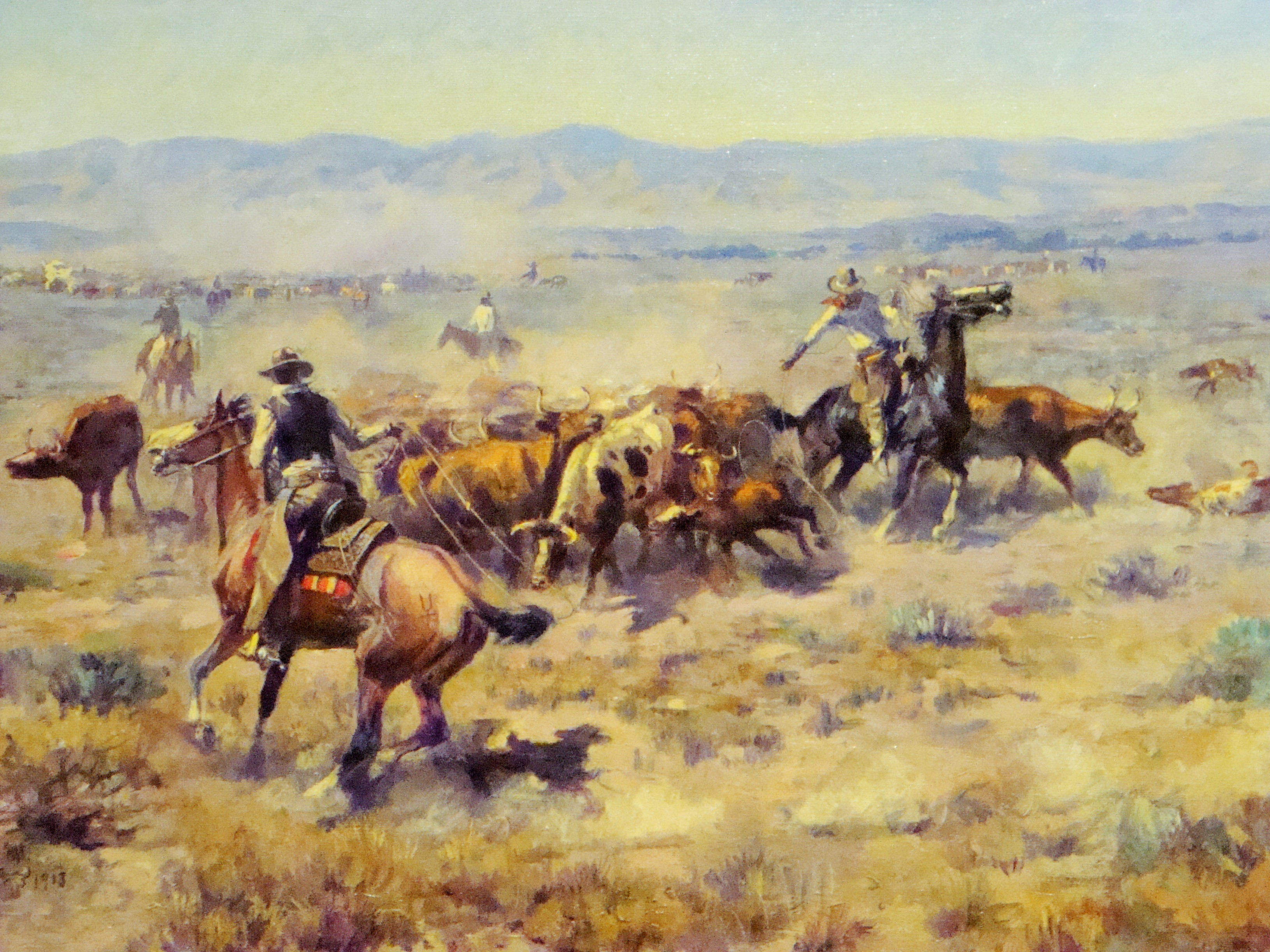

People often treat Charlie Russell paintings like photographs: accurate representations of Montana’s cowboy past. In reality, Charlie Russell witnessed very little of the era that he painted. Born in 1864, Russell came to Montana in 1880. By then Butte’s industrial machine had replaced panning for gold, and only a few obstinate trappers still struggled to make a living off the fur trade. Within ten years of his arrival, two transcontinental railroads crossed the new state, and the buffalo were almost extinct. Between 1909 and 1925 when Russell’s talented bloomed, farmers filled the Northern Plains (until drought turned the area into a dustbowl), cars filled the roads, and airplanes—well they might not have filled the sky, but they certainly made the sky more crowded than you would suspect from a Russell painting. Russell paintings aren’t exact representations of the world, they are representations of turn-of-the-century angst. They tell a story of a past that Russell remembered, that he had heard about, and that he longed for.

A preservationist to his core, Russell used both his paintings and his stories to save the remnants of the fading idea of the frontier.

And I for one am glad he did.

I took these pictures at the Montana Historical Society in Helena, which has a huge collection of Russell art. You should also visit the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls, which has over 2,000 Russell paintings and artifacts.

As usual, I got most of my information from essays in Montana: The Magazine of Western History, including “The Conservatism of Charles M. Russell” by J. Frank Dobie, as well as “A Dedication to the Memory of Charles M. Russell 1864-1926” and “…I Feel I am Improving Right Along” both by Brian W. Dippie.

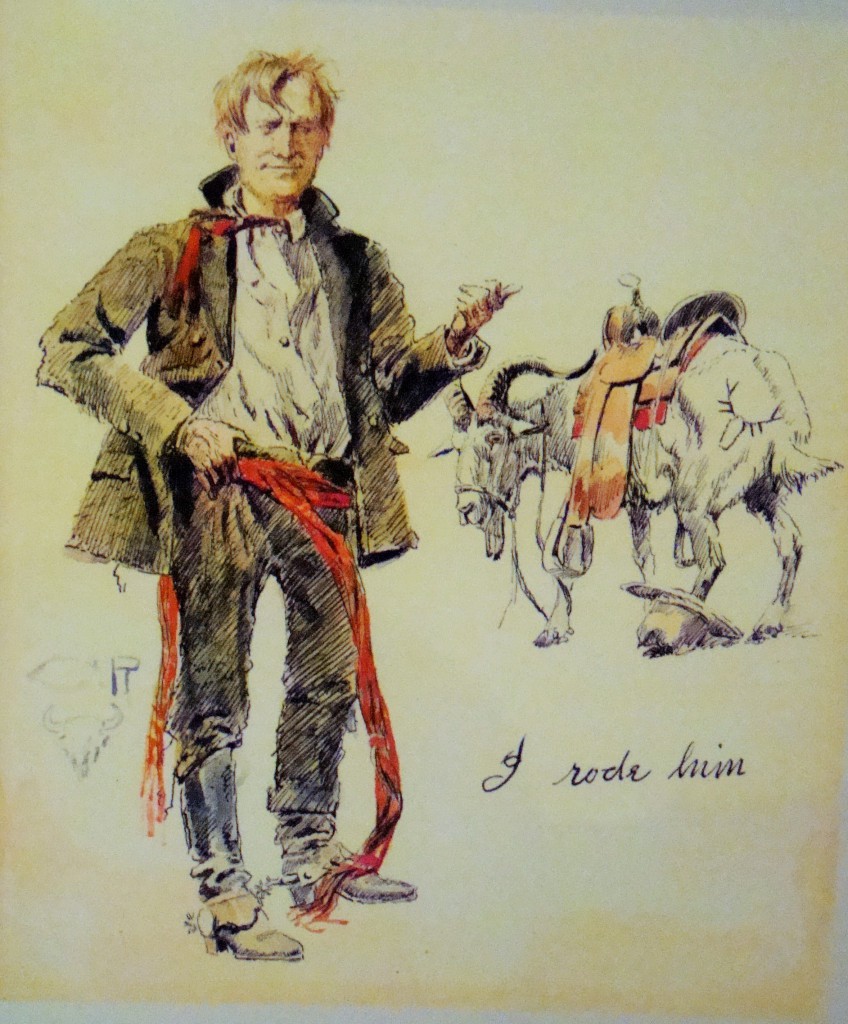

I have a Statue of “Charlie Russell with the Goat and I Rode Him” still. filled with Booze! How much is this worth?

REPLY PLEASE!

I have one of his paintings that was painted in 1913 I was wondering how much would be . The. frontier

How much is the original Charles Russell a Roundup 1913 worth

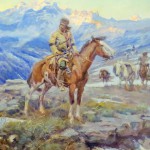

I have a painting on canvas signed by Russell there is debate between my husband and as to weather or not it’s a actual painting or reproduction. Any suggestions on how we can know for sure. I say painting because you can feel the bumps from the paint. It is the same image as the man on horseback top right corner.