Oddly, the Baroque gables and adobe walls of Boulder Hot Springs don’t look out of place nestled in the foothills south of Boulder. Something about Montana’s arid landscape lets the Alamo-esque style make sense. A little surprising, perhaps, but not outrageous. One could even assume, based on our state’s name and a number of historic buildings that look like they were plucked wholesale from the California countryside, that Montana must have some Hispanic heritage. One would be wrong of course, but one could still assume.

In fact, there is no Colonial Spanish heritage in Montana since Spanish explorers never made it to the area. Montaña means mountain or mountainous in Spanish, and was proposed by a congressman from Ohio when the area applied to become a territory. Other congressmen protested the name on the basis that a) the name suggested a non-existent Spanish heritage and b) over half of the territory was pretty darn flat. However, these arguments were ignored because (I assume) the bylaws of Congress forbid logic in its august halls.

Like the state name, Spanish and Moorish style architecture appeared in Montana without any history. In 1884 Helen Hunt wrote a serialized novel called Ramona that romanticized life in the old Mexican missions. In 1885 John Ormsby published a very popular translation of Don Quixote. Two translations of The Arabian Nights appeared around the same time (one in 1882 and one in 1885). These books illustrate the surge of interest in Spanish and Moorish arts and styles that swept the nation, especially in the world of architecture.

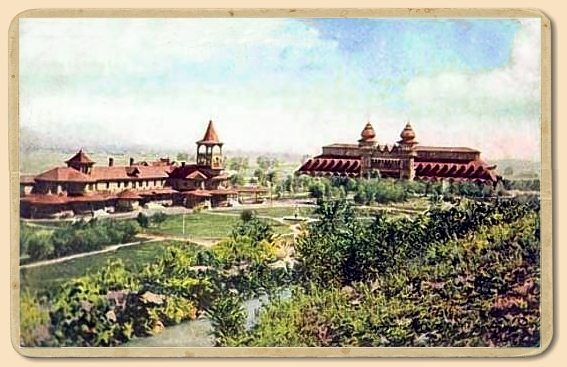

According to art historian Hipólito Rafael Chacón, the Moorish style emerged first, and quickly became associated with places designed for vacation and relaxation, for example: the Broadwater Natatorium in Helena, a decadent and ostentatious building that makes the Sultan’s palace from Disney’s Aladdin look positively reserved. Another, still standing, example of Moorish style is the Helena Civic Center, which was originally commissioned as the Algeria Temple by the Ancient Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (Shriners).

Mission Revival style was popular across the country from the 1880s to the 1920s. It is usually subtler than Moorish architecture, and more widespread across Montana. This is where you get the Alamo-esque embellishments (which I found out are called curvilinear gables or parapets). Terra cotta roof tiles, long arcaded patios, and adobe (or fake adobe) walls also characterized Mission Revival style. Boulder Hot Springs is a perfect example of this. Originally built as a Queen Anne style hotel, the owner commissioned a major renovation in 1910 to make it look more like a California mission. Buildings across the state reference Mission Revival. Examples include MSU’s Hamilton Hall (c. 1910), some of the buildings at Fort Missoula (c. 1911), as well as a number of civic buildings and movie theaters across the state.

Chacón suggest several reasons for uses of Mission Revival in Montana. Two interest me. On the one hand, using Mission Revival style put Montana on the cutting edge of fashion. On the other hand, it was a distinctly Western (albeit Southwestern) style, and using it allowed Montanans to assert their sense of regional identity. Once you start looking, it is easy to find countless beautiful buildings that reference what Chacón calls Montana’s “mythic past.”

Most of my research for this piece came from “Creating a Mythic Past: Spanish-Style Architecture in Montana” by Hipólito Rafael Chacón in Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Autumn 2001.

As a native of San Antonio, Texas I am always captivated by allusions to “Alamo-style” architecture. What many folks don’t realize is that the world-famous facade of the Alamo (the “curvilinear” motif) was in fact designed by a U.S. Army engineer tasked with rebuilding the chapel roof so that the space could be used by the U.S. Army garrisoned there for munitions storage in 1847 after Texas had joined the Union (1845). The original chapel roof had already begun to collapse when the Texicans (Crockett, Travis, Bowie et al) took brief possession in 1836. Subsequent bombardment by Santa Anna’s forces during the siege and Col. Bowie’s last-ditch intentional detonation of the defender’s black powder reserves finished the job. Sketches of the Alamo drawn weeks and months after the siege show the destroyed front parapet, with no hint of its original form. That restored facade may now be among the most iconic in the world.