Frank Linderman came to Montana 60 years too late. Linderman moved to Montana in 1885, at the age of 16. He came to escape the confines of civilization, looking for adventure and wilderness. Unfortunately, as we all know, Montana was a completely tame and civilized place by 1885. Ok, so that’s not entirely true. After all, with a third of the state in public land and less than seven people per square mile, I’m not sure that Montana counts as civilization even today. But 1885 Montana was tamer than the Montana Frank dreamed of. Railroads sliced across the state, cattle had replaced buffalo on the plains, Butte was on the rise as one of the west’s most important cities, oh and his dream profession—Mountain Man—had gone almost extinct some 30 years previously.

Nevertheless, he headed west for the Swan Valley—looking at a map, he had decided that it was about as from civilization as one could get. According to the story he wrote in Learning a Hunter’s and a Trapper’s Art, Frank found a mentor by camping near an old time trapper named Hank Jennings, the same way Jane Goodall studied chimpanzees. Jennings seems to have adopted Frank as a protégé without really realizing it.

I first read Learning a Hunter’s and a Trapper’s Art while looking for descriptions of fur trapping practices. For that purpose, the story is great. They built a cabin and a dugout canoe, they laid trap lines, mixed beaver bait, and trudged through the snow on homemade snowshoes. Anything you want to know about fur trapping in the 1880s, Linderman covers it.

However, Linderman was more than an adventurer and talented historian, he was also a tireless humanitarian and an outspoken advocate for the land. Because Art describes his first foray into the wilderness we get to watch Linderman’s character develop. He keeps his tone conversational, and only rarely includes reflection, as when he describes meeting a band of Flathead Indians:

“I think it was the cabin, however, that encouraged their feeling that we had intruded upon their rights, its appearance of permanency foretelling the loss of the Swan River country as a hunting ground. But that time was yet a long way off.”

For the most part, however, he keeps to the stories, letting events speak for themselves without much in the way of explication. In his careful details we can witness his love for the animals he hunted, the land he crossed, and the (very few) people he encountered.

Like his friend Charlie Russell, Linderman came to the west too late. The heyday of the mountain man had run from the 1820s to the 1830s, and by the 1880s it was hardly a sustainable occupation. He lived the loose-footed life of a mountain man and cowboy for only a few years before settling down to other work: a guide, an assayer, a journalist, a politician, a writer, and a humanitarian. His many writings include books that carefully describe the history and myths of Montana Indians. He worked tirelessly in the creation of the Rocky Boy’s Reservation for then landless and ignored Chippewa and Cree. Learning a Trapper’s and a Hunter’s Art is the only work by Linderman that I have read, but the short story showed a fascinating glimpse into a man with a passion for Montana’s land and people.

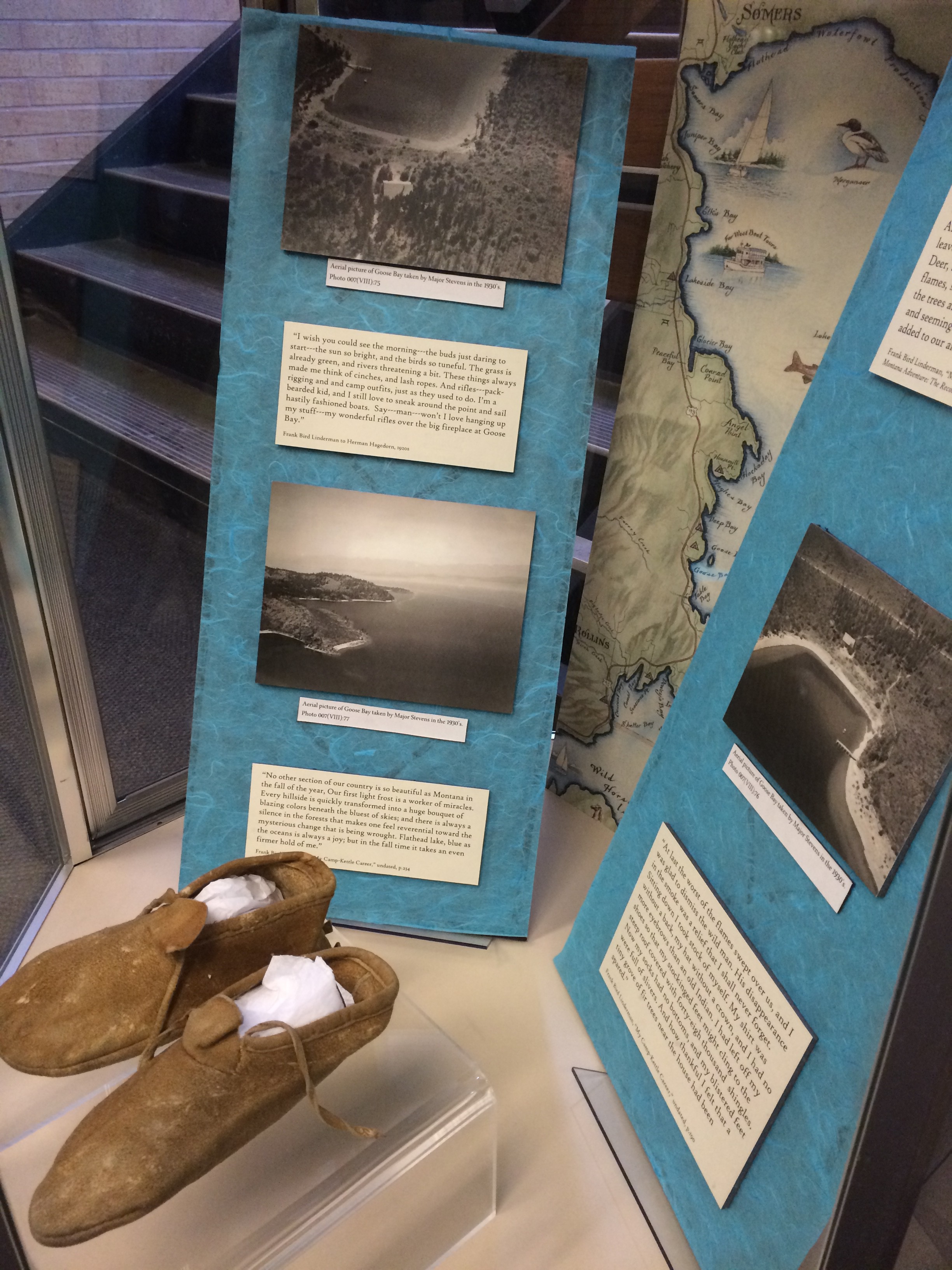

For more information about Linderman, check out his list of books on Amazon, and the Linderman collection in the Mansfield Library Archives and Special Collections at the University of Montana