Neither Empty Nor Unknown

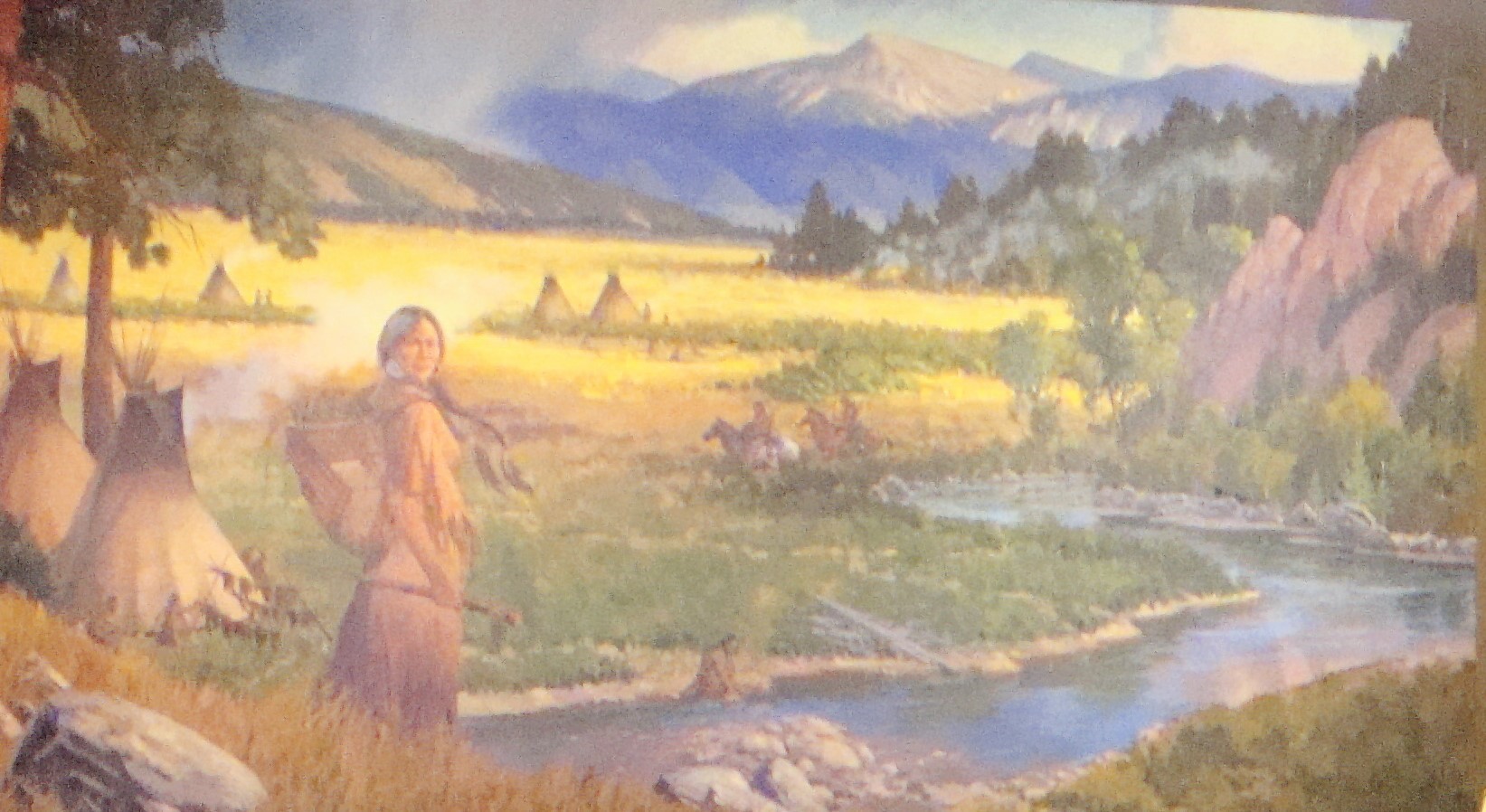

Editor’s Note: These are the kind of posts that happen when you turn a history major loose in a museum. These posts were inspired by, and draw heavily on, an exhibit at the Montana Historical Society in Helena. Neither Empty Nor Unknown is an incredible exhibit that examines what life in Montana looked like during the time of Lewis and Clark.

It is easy (for me, at least) to think of the pre-Lewis and Clark west as a land in stasis, a land frozen until the “Corps of Discovery” chanced upon it. We do not have written records of the land that would become Montana from before 1803. We do have oral histories and archeological evidence, but in a culture that relies so heavily on the written word, these sources can be difficult to come to terms with. Add this to the fact that Lewis and Clark believed they traversed a pristine virgin wilderness and thinking about Montana as a land in stasis becomes understandable. Completely wrong, of course, but understandable.

Pre-history

In 1969 two construction workers unearthed the oldest human remains in North America at the base of a sandstone cliff a few miles from Wilsall, Montana. The remains of the two year-old boy were buried with a cache of weapons, including atlatl shafts, tools, and Clovis spearheads. The remains and cache date from 11,000 years ago. Thirty years earlier, workers outside of Helena discovered Folsom culture artifacts, which date from 10,000 years ago. These sites suggest a long history of human occupation in Montana.

The next evidence of humans in Montana is a picture of a turtle on the wall of a cave near Billings, in Pictograph Caves State Park, which dates to around 2,100 years ago. Organic matter taken from pictographs in the Gates of the Mountains Wilderness Area are believed to be 1,300 years old. The buffalo jump at First People’s Buffalo Jump State Park contains evidence of nearly continuous use for the last 1,000 years. Taken together, these discoveries suggest that humans have lived in Montana for a very long time, certainly for the last millennium, and probably for much, much longer.

Early Modern

In 1492, Christopher Columbus reached the outskirts of the Americas. Nomadic tribes sparsely populated the Northern Plains, following the buffalo herds. Salish territory, for example, straddled the Continental Divide, they spent part of the year in the plains, hunting bison, and other parts of the year digging camas in the mountains to the west. The Shoshone, the Kootenai, and the Kalispel probably followed similar patterns. The Blackfeet, who speak an Algonquin language, may have originally lived east of the Northern Plains, perhaps in the lake region of Canada, and may have travelled to hunt bison on the plains as well. It would be another two and a half centuries before any Europeans might have reached modern-day Montana, and a full three centuries before we have any definitive proof that they did so. Yet Montana began to experience the consequences of European expansion long before then.

In this and subsequent posts, I have decided for the purposes of clarity to use the English names of the tribes. For more on Montana’s Native Americans, see my previous post Montana’s First Residents. Follow these links to read “Montana at the Time of Lewis and Clark” Part 2 and Part 3.